|

|

London North Western

Railway:

Midland

Railway:

Stratford

Midland Junction Railway

|

|

LMS Route: Rugby to Wolverhampton

The Rugby to Wolverhampton route was essentially built by

two railway companies, the section from Birmingham (Curzon Street) to London

via Rugby being built by the London & Birmingham Railway (L&BR)

whilst the section from Birmingham New Street to Wolverhampton was built by the

Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Stour Valley Railway Company under the

auspices of the LNWR. The L&BR, together with the Grand Junction Railway

and the Manchester and Birmingham Railway, having merged together to form the

London & North Western Railway whilst the BW&SVR line was acquired by

the LNWR. The section of line between Curzon Street (the original L&BR and

GJR termini) and New Street was built by the London & North Western

Railway.

The following is an extract from one of Reg

Kimber's scrapbooks compiled over 50 years.

The Evolution of the Premier Line

LONDON AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY CENTENARY

An article by TB Fowler which appeared in the

Coventry Evening Telegraph on 17th September 1938

WHEN the London arid Birmingham Railway was opened in

its entirety, on September 17, 1838, the promoting company secured the dual

distinction of owning the first main line to enter London, and the longest

railway system then in existence - 112 ¼ miles.

At the time it was

visualised as the great trunk railway from London to the North, but the

developments in transport services that were witnessed imparted to the

enterprise a significance, far exceeding anything the promoters' had

anticipated.

Branch lines from Blisworth to Northampton and Peterborough,

and from Coventry to Warwick and Leamington and later the Birmingham and Derby

Junction Railway linking up at Hampton-in-Arden, provided arteries through

which traffic of all kinds poured in a continuous stream.

Moreover, the

Grand Junction Railway from Birmingham to Liverpool; the Liverpool and

Manchester, with such subsidiary lines as the Warrington and Newton; the Wigan

and Preston; Preston and Lancaster; and Lancaster and Carlisle, some of which

had been planned without any relationship to the others, opened up facilities

for direct communications between London and Carlisle, a distance of 299

¼ miles.

Promoters' Long Struggle

Thus - the way was paved primarily for the union of

the London and Birmingham and Grand, Junction railways under the title of the

London and North Western Railway, and eventually for the great grouping scheme

which brought eight constituent and 27 subsidiary companies - owning 6,334

route miles, and 19,383 track miles, into the London Midland and Scottish

system.

It is on record that no private Bill was ever more strictly

scrutinised than that of the London and Birmingham Railway in spite of the

weight of argument brought to the support of the proposal by industrial

interests, which were suffering heavily from the lack of adequate means of

transport, it took two years to get the Act sanctioning the undertaking through

Parliament, and from first to last, the most determined opposition had to be

encountered both in and out of the House of Commons.

While the work of

construction was in progress anxieties and difficulties accumulated. Almost

immediately there was a big jump in the price of materials. At one period seven

contracts were thrown on the company's hands. A sum of £370,000 more than

was bargained for had to be paid for land, the price averaging £315 per

acre in the Birmingham area, and £335 per acre in London. Up to January

1838, the expenditure, as a result of unexpected troubles had exceeded the

estimates by nearly one and a half millions, aggregating £3,931,829.

Both at Euston and, the Birmingham terminus at Curzon

Street imposing station buildings were erected. The structures in each case

were of bold design, with Doric porticos, and the new notes struck in, this

direction, as well as in the engineering works and general constructional

details, - added to the public interest with which the opening of the line, was

regarded.

As early as 7.15 a.m. on the chosen day a special train left

Euston for Birmingham for the inaugural run the passengers including Mr George

Carr Glyn, the chairman of the Company, together with the directors and

visitors, Mr Stephenson, the, engineer, Mr Bury, the locomotive superintendent,

and Mr Creed, the secretary, while HRH the Duke of Sussex travelled with the

party as far as Rugby.

The visitors spent one hour in Birmingham, and then

returned to Euston, where a ceremonial banquet was held.

All along the route

the greatest of enthusiasm was displayed, and the passing of the first ordinary

train, timed to leave London at 8 am., was the signal for local festivities at

all the stations on the new part of the railway.

Change was the order of the

times, and Denbigh Hall station, a well- known landmark.-was demolished, the

materials being used in the building of the station at Bletchley.

Notable Railway Administrator

But it was in the increased power and influence of the

railways that that most convincing results, were achieved, The London and

Birmingham succeeded on its merits. As indicated, it was well served by its

branches and a further strengthening factor was found in the Midland Counties

line, which, joining up at Rugby on July 1, 1840, handed over its traffic from

Derby, Nottingham, Leicestershire, and the north for conveyance to

London.

As an independent line, the London and Birmingham Railway lasted for

eight eventful years, and when the merger with the Grand Junction was effected,

its chairman, Mr. Glyn, continued to act in the same capacity with the London

and North Western.

The new and large company became, from its inception, a

challenging force in the railway world. Owning what was given the proud title

of the "Premier Line," though of less mileage than the Great Western, and

smaller capital than the Midland it was able to show the largest annual revenue

and was richest in rolling stock.

It was particularly fortunate in its

executive, at the head of which stood Captain Huish, one of the most able

railway administrators and diplomatists of the age. A masterful man. Captain

Huish was as enterprising as he was resourceful, and he was responsible for

important developments in several directions, though his methods sometimes

exposed him to sharp criticism.

In 1846 the London and North Western Company

established at Crewe the largest and most complete locomotive works in the

Kingdom, and here the genius of such famous locomotive engineers - as Francis

William Webb and George Whale found expression in engine designing on a scale

and of a standard that excited the envy, if not always the admiration of

rivals.

Innovations and Changes

Webb was the originator of the track trough system;

which enables expresses to take up water while travelling at speed, and, apart

from introducing this innovation, the London and North Western was the only one

of the principal railway companies to apply names to all its express

locomotives.

The earlier railway plans affecting Birmingham had contemplated

the erection of separate stations for the London and Birmingham and Grand

Junction Companies in Broad Street. Curzon Street, however, offered a better

point of entry into the city, and in the plans of 1831 this locality was

favoured for the central station. But in the light of subsequent expansions

attention was directed to New Street, and on June 1st, 1854, the station here

was opened for all passenger traffic, and Curzon Street became a goods station

only.

In one other respect the London and North Western was conspicuous,

holding the monopoly of the through route from London to the north until 1850.

The whole career, of the London and Birmingham railway was worked out amidst

the, changes and, chances of transition. Conceived when prejudices against

railways ran deep and strong, it contributed in ways of its own to the

revolution represented by the public surrender to the magic of speed. |

The London and Birmingham Railway

A bit of history from 1839 by Chris Heaven

The cost estimates for the building of the 112½

mile London and Birmingham Railway were hopelessly optimistic. The original

incorporating Act of Parliament had authorized the raising of £2,500,000

via £100 shares. However by the time the line from Euston Square to

Curzon Street terminus in Birmingham opened as a through route on 17th

September 1938 two further Acts had been needed to raise the capital to

£4,500,000. [The company had obtained £2,375,000 from shareholders

and £2,125,000 via loans.] This still proved inadequate and in the spring

of 1839 the railway had another Bill before Parliament seeking authority to

raise a further one million pounds through a third share issue. The minutes of

the evidence taken during the committee stage of this Bill, in March and April

1839, provides a fascinating insight into the early operation of the railway.

The main aim of the committee was to lay bare the financial position of the

company and to determine whether or not the raising of this extra capital was

really justified. However the dissecting questions put by legal council to the

company secretary, general superintendent and one of the directors also reveals

a lot about the operational arrangements at a time when, just like the

embankments, things were still bedding down.

The interrogation of the railway officers revealed

that the company had been somewhat devious in the way it had raised its funds.

It had also exceeded the authority Parliament had given for this. Mr Creed the

company secretary was forced to admit that beyond the £4½ million

approved capital the railway had other borrowings and debts, as at 15/3/1839,

of £631,000; or maybe more. Much of this borrowing had been secured

against future revenue. It was therefore rather presumptive to come back to

Parliament with a request to raise an additional £1million when the

railway had actually already spent around 2/3 of this sum. Parliament was

hardly able to refuse and allow the endeavour to fail.

Existing share holders had not been required to pay

the full amount for each share. For the original £100 shares only

£90 had been paid up. These shareholders were then offered, pro-rata,

£25 shares for which they only had to pay £5. The remaining amount

had been borrowed against the security of a call upon the shareholders for the

outstanding value of the shares. This put the holders of the £25 shares

in a very favourable financial position. They received a dividend on the full

£25 share value yet had only paid out £5. In the 6 months since the

full opening of the railway this had given a 35% annualized return on the

£5 investment. Knowledge of this had inflated the value of these shares

which could be sold at a very healthy profit. However if the shares were

retained and the loans then paid back out of the general revenue of the company

the shareholders might never have to pay the remaining £20. The company

officials had to admit that this arrangement for raising funds by borrowing

rather than calls upon shareholders had been wrong. Their excuse was that if

they had not done so construction would have been delayed or postponed. The

committee tried to impose ways to correct the matter but legal council insisted

that this was impossible without breaching legal obligations to lenders and

upsetting the general money markets. It was agreed though that future share

issues would not be managed in this way.

The questions put by the opposition lawyers reveals a

mentality stuck in the canal and turnpike era. No doubt this would change

dramatically in the coming years. The peak of the railway “mania” was

less than a decade away and 1846 was to see the greatest number of railway Acts

submitted to Parliament in a single year at 271. They seemed unable to grasp

the concept of a unified fare covering all the cost of a journey on the line.

Repeatedly the company officials are asked what part of the charge was for

“the toll” and what for “locomotive power”. The company

accounts were not ordered in a manner able to answer this. The London and

Birmingham was principally a passenger railway. At the time of the committee

hearings, six months after through route opening, it was running 7 trains on

weekdays and 4 on Sundays in each direction. There were 4 classes: second class

open, second class closed, first class and the mail coach (the most

prestigious). “Open” meant no protection whatsoever from the

elements. This was basically a 4 wheeled truck with benches and capable of

carrying up to 24 passengers. The “closed” second class carriage was

used with the night mail train. The fares for the full trip were 20s, 25s, 30s

and 35s respectively. This was about 2d, 2½d, 3d and 3½d per

mile. The most profitable were the second class passengers. This was simply

because more could be crammed into each carriage and these carriages cost much

less to manufacture and maintain. The unlined (i.e. non-upholstered) second

class carriage cost £130 to £150. In comparison the first class

carriage cost £460 to £480 and accommodated only 18 passengers.

These were more prone to wear and tear and needed repainting and relining at

least annually. The mail coach cost £500 to £520 and had a coupe

for 2 and a compartment for 4, with 2 to 4 outside seats. An audit during

October 1838 showed the ratios of passengers, mail : first : second as 1 : 2.5

: 3.2, i.e. one mail coach passenger for every 3.2 second class passengers with

a average fare of around 2¾d per mile. When compared to airlines today

this is a healthy proportion of higher tariff passengers. The fact that the

railway was making little profit from the more prestigious clients suggests

that the fare differentials were too low, i.e. they weren't charging enough for

the first and mail passengers. The committee suggested that the railway

revenues might improve if they lowered fares to attract more passengers. There

had been a debate amongst the directors about this but it was a dangerous

strategy. Mr Boothby, the director examined by the committee, stated that if

fares were reduced by 1/3 it would be necessary for the traffic to double to

generate the same dividend. Indeed when the line had been partially opened from

London to Tring in September 1837 the fares had been much lower and the railway

had operated at a loss.

At any rate trains were running well below capacity.

The average loading was 55 persons per train whereas if full of second class

passengers the maximum was around 200. The journey time between London and

Birmingham was 6 hours for first class trains (stopping only at principal

stations) and 6½ hours for second class trains stopping at all stations.

The fastest train was the day mail which did the journey in 5 hours which is an

average speed, including stops of 22.5 mph. This was barely twice the fastest

stage coach of the era at a time when the main turnpike roads were in generally

good order.

The dedicated first class trains highlighted social

class divisions and prejudices. Quoting directly from the minutes, “Q:

Would there be any objection. . .that one second class carriage be attached to

each first class train? . . . complaints are made, on the part of gentlemen,

that servants, when traveling by a first class train, are frequently placed by

the side of ladies in the same carriage, sometimes eating a mutton chop, and at

other times a pork pie; besides which, gentlemen are obliged to pay the expense

of the first class train for their servants. A: . . .the board (of the railway)

has provided, outside the first class carriages, seats in which they may put

their servants at the second class fares.” The outside seats were placed

high up at the ends of the carriages in the manner of stage coaches. This was a

very exposed position and one can imagine the experience passing through long

tunnels at the slow running speeds. A concession to female servants on these

first class trains was that they were allowed to ride inside at second class

fare.

The conveying of horses and their carriages was the

most unprofitable traffic. The power needed to draw one horse in a box was

thought greater than that to pull a passenger (railway) carriage. Gentlemen's

carriages and horses needed to be at stations at least a quarter of an hour

before the time of departure. Trucks (flat wagons) were kept at the principal

stations but to prevent disappointment it was recommended that these should be

booked in advance. The rate for a carriage with four wheels was 75s for the

whole distance, but if two carriages with two wheels could be placed on one

flat wagon this was only 55s. The fare for a horse from Birmingham to London

was 50s, i.e. the same as one second class + one first class passenger, but

requiring its own box. Passengers that remained either in or on gentlemen's

carriages, and grooms in charge of horses were charged second class fares. This

was the motorail service of the 1830s.

The secretary was asked about speeds on other railways

and he thought the Liverpool and Manchester managed 30mph, and the GWR 35mph.

His excuse for the relative slowness on the L&BR was the need to pass

carefully over some of the embankments which were still consolidating, and the

disciplines of adhering to a published timetable. In places speed restrictions

were 10 mph or less (where now Virgin pedolinos whisk by). The evidence often

makes comparison with the Grand Junction Railway, which ran from an adjacent

terminus in Birmingham to Warrington and thence to Liverpool and Manchester. At

this time that railway used a starting departure time but unlike the L&BR

didn't wait for time at intermediate stations and had a generally poorer

punctuality record.

During these first months it was proving impossible to

accurately predict the cost of operating locomotives. The plan had been for Mr

Bury (of Liverpool) to manufacture and run locomotives under contract at a

farthing per passenger mile and ½d per ton of goods per mile. This was

based on early experience with the Liverpool and Manchester railway. These

figures were quickly found to be invalid. Even on the L&MR locomotive costs

rose substantially after 3 or 4 years when heavy repairs to the engines became

necessary. On the L&BR the higher cost of coal and poorer than expected

passenger numbers were other factors that pushed up motive power costs. The

anticipated increasing speeds would also raise fuel consumption and increase

wear and tear on locomotives and track. By April 1839 the figure had reached 7

shillings and 16 pence per passenger mile and was still rising. The idea of a

contract was dropped and Mr Bury's services were hired on a salaried basis and

the company itself took direct control of locomotive finances.

Mr Boothby (company director) reported that

locomotives for passenger work were of a different power from those intended to

convey merchandise. They were all of the 4 wheeled type as was the case on the

Liverpool and Manchester, North Union, London and Southampton, Bolton, and

Midland Counties railways at this time. The only 6 wheeled engines on the

L&BR were for ballast trains. The Grand Junction Railway however used

exclusively 6 wheeled engines. Robert Stephenson, chief engineer for the

L&BR, was an advocate (and manufacturer) of 6 wheeled locomotives. The

company may not have wished to be unduly dependant on him and thus turned to Mr

Bury for its locomotives. Much of the questioning was to determine how open to

competition the L&BR was. This included whether they would allow

locomotives from other railway companies to operate on the line. Much of this

revolved around practical issues such as access to water and station

facilities. The company officials conceded that the legislation allowed others

use of their facilities but in reality they were not going to let this happen

easily. They insisted that any individual arrangements they had already made

did not set a precedent for everyone else and that water would only be supplied

at an appropriate price decided by them; otherwise let them build their own

stations and pipe-work. They were quizzed as to whether the GJR's 6 wheeled

locomotives would fit on the L&BR turnplates but not definitive answer was

provided.

In the transport of goods the role of the railway was

just to provide the locomotives and wagons. It was not itself “the

carrier”. If the public wished goods to be sent via the railway this was

organized by other businesses that also took care of the movement of goods to

and from the railway premises. These carriers in effect purchased capacity on

trains and were obliged to cart items away from stations within 6 hours of

arrival. The Bill (i.e. the request to raise more money) was opposed by one

such carrier, a Mr John Robins. His objection was that the railway was giving

preferential treatment to Pickfords and Co, who would been the sole carrier

when the line first opened. [Some of the evidence given did suggest that they

had enjoyed a generous mark up on the carriage of some goods and that

competition from other carriers would bring charges down; both on the railway

and canal.] Mr Robins claimed that the railway was not honouring its legal

obligation to allow free and fair competition and to deal with all users of its

facilities on even terms. Initially the company denied this but questioning

quickly revealed a conflict of interest in that the General Superintendent of

the railway, a Mr Baxendale, and a share holder in it, was also a partner in

Pickfords and Co. The committee put pressure upon the railway officials to be

more overtly and fairly open to all carriers. A general fee structure for all

carriers could not be agreed because of the issue of empty wagons traveling

back from London to Birmingham – and who should pay for this. In the

transport of goods the railway was in competition with the canals. The railway

was more expensive but offered greater speed. There was a demand to hurry goods

from the north to London for sale or export. There was less to transport in the

other direction and less of a rush. There was therefore unused capacity within

the wagons returning to Birmingham and the company suggested, as an experiment,

charges to carriers of 30 shillings per ton from Birmingham to London and 33

shillings in the opposite direction. Understandably not all carriers were happy

with this.

The average daily movement of goods between September

1838 and March 1839 was 72 tons 6 cwt. Nowadays this could be done by two

lorries! The railway was only interested in handling the more lucrative general

merchandise and in relatively small amounts. There was no intention to

transport heavier goods such a stone and coal. The canals could do that. The

company provided wagons and locomotive power at a charge of 12s a ton per round

trip, to and from London and Birmingham. These figures are a little at odds

with those above but this may be because they do not include the

“toll” component, i.e. the access charge. Freight charges seem to

have been in a state of flux because of the uncertainty over locomotive costs.

A wagon could carry up to 4 tons but this was soon restricted to 3½

tons. Loading was though not to be less than 2½ tons. One locomotive

could only manage a train of 100 to 120 tons. Where necessary double heading,

rather than banking was used. This was recommended if a passenger train

consisted of more than 12 carriages, or 14 in good weather.

Fare dodging had been frequent in the early days, both

from passengers traveling in a higher class of carriage or beyond the

destination which their ticket allowed. “As much as £50 or £60

had been recovered in one week.” The practice had been curtailed somewhat

by requiring tickets “to be presented at the last station before London or

Birmingham”. Checking tickets in transit was considered impractical as it

would have involved employing a guard in each carriage.

When asked about cost comparisons with other railways

Mr Boothby (company director) gave figures per mile of £24,000 for the

Grand Junction Railway, £42,000 for the Liverpool and Manchester and

around £50,000 for the L&BR. His justification for the differences

were that the quantity of earthworks on the L&BR had been nearly four times

that on the GJR, with numerous expensive tunnels, viaducts, embankments and

cuttings. There were large over spends (and delays) on Kilsby tunnel and

Blisworth cutting. The 1¼ mile extension from Camden to Euston had been

particularly expensive at between £300,000 and £400,000 once

property purchases were included. Not one of the 30 main contracts had been

completed to budget. For all of this the humble navvie was paid 4/6

(22½p) a day + beer.

The Act authorizing the requested additional

£1million was passed on 14th June 1839 but, in the words of John Britton

in his account of the line published that year, “granted (only) after a

long and searching investigation into the affairs of the Company”.

|

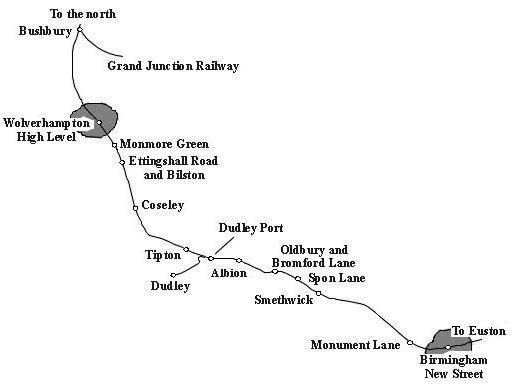

The Stour Valley Line

An overview by Bev Parker

Beginnings

It was originally known as the Birmingham,

Wolverhampton & Stour Valley Railway, its construction was authorised by an

Act of Parliament passed on 3rd August 1846. The capital was equally divided

between four sources; the company itself, the Shrewsbury & Birmingham

Railway, the Birmingham Canal Company, and local interests. The line was to

start at New Street station which was initially known as Navigation Street

station until its name changed in timetables in November 1852. The route was to

run from the London & Birmingham line at New Street station to Bushbury

where it would join the Grand Junction Railway. There would also be a short

branch to Dudley from Dudley Port. There were seven intermediate stations;

Smethwick, Spon Lane, Oldbury & Bromford Lane, Dudley Port, Tipton,

Deepfields & Coseley, and Ettingshall Road & Bilston. The route was

called the Stour Valley Line because of a projected line from Smethwick through

the valley to Stourbridge, which never happened. Right from the beginning the

London & North Western Railway wanted to gain control of the line, which

after all ran from their station at Birmingham to the old Grand Junction line

which was also in their possession. It strengthened its control in three

ways:

1. It took over the Birmingham Canal Company.

2.

It leased the line under the terms of an Act passed on 1st July 1847 which

would prevent the Shrewsbury & Birmingham from using the line if they

joined the Great Western Railway, who were intense rivals of the London &

North Western.

3. By making the Wolverhampton General station (High Level)

and the section to Bushbury joint property with the Shrewsbury & Birmingham

in an Act of 9th July 1847, which also gave the Shrewsbury & Birmingham

running powers over the Stour Valley Line.

Having secured control of the line they could begin

its construction.

Construction

This was split into three sections; Birmingham to

Winson Green, Winson Green to Oldbury, and Oldbury to Bushbury. The engineers

in charge were Robert Stephenson and William Baker, and initially work

proceeded briskly. Their report of August 1847 indicated that one third of the

845 yard tunnel into New Street was already complete. Having secured control of

the line, the London & North Western were in no hurry to complete the task

and so the remaining work proceeded at a more leisurely pace. The progress was

also slow on the section near Bushbury due to difficulties in acquiring land.

Work finished on 21st November 1851, and was officially announced on 1st

December, it had taken just over four years.

Running

After the December announcement the Shrewsbury &

Birmingham fully expected to start running their trains into Birmingham, but

the London & North Western had other ideas. On the 10th January 1851 the

Shrewsbury & Birmingham signed a traffic agreement with the Great Western

Railway which led to an offer to amalgamate in 1856 or 57. The London &

North Western had heard about this and so invoked the terms of their 1847

agreement. They denied access to the Shrewsbury & Birmingham which set the

scene for the bitter dispute that followed. On 1st February 1852 the line was

opened for London & North Western goods, and from 1st March 1853 a half

hourly service started from Wolverhampton to Birmingham which was designed to

prevent the Shrewsbury & Birmingham from gaining access . The London &

North Western claimed that due to the frequent service it would now be

dangerous for Shrewsbury & Birmingham trains to run alongside their own.

The Shrewsbury & Birmingham finally accepted an arbitration award that set

a high fixed rent for their use of New Street station and their trains started

running to Birmingham on 4th February 1854. They finally joined the Great

Western on 1st September 1854, and were granted an extension which allowed them

to continue to run their trains on the Stour Valley line until the Great

Western line could be opened. In the event it remained closed until 14th

November 1854 because a bridge had collapsed at Handsworth.

After opening, several new stations were quickly

added, they were:

Bushbury on 2nd August 1852

Albion on 1st May

1853

Monument Lane on 1st July 1854

Monmore Green on 1st December

1863

Once the Shrewsbury & Birmingham had departed,

the line soon became a great success. In the 1870s as many as 120 passenger

trains and 50 goods trains ran daily in and out of Wolverhampton. |

|